|

Nick Bullock

Тибет, Nyainqentangla Юго-Восточная (7046 м) по Северному контрфорсу. Nyainqentangla South East via the North Buttress.

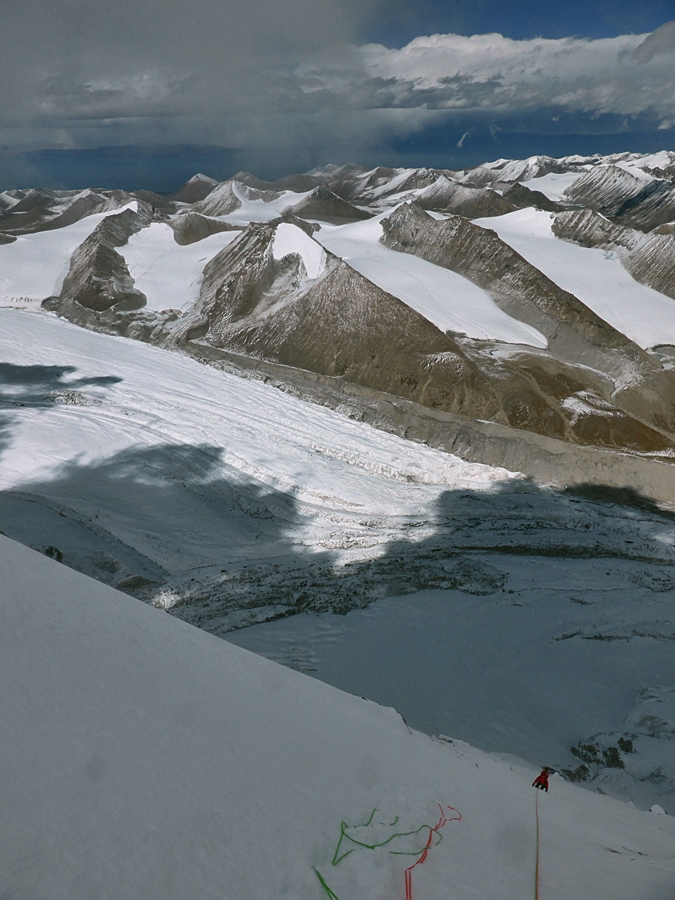

The North Buttress of Nyainqentangla South East first ascent by Paul Ramsden/Nick Bullock. 1600m. ED+ Я сидел в палатке и сине-полосатом брезенте, нашем импровизированном доме. Пол Рамсден сидел рядом. Слева от нас стремительная ледниковая река билась о серые скалы – их выгладил постоянной серый поток. Мы были первыми людьми с Запада, пришедшими сюда, чтобы осмотреть эту долину к северу от вершин Nyainqentangla. "Нет, с этой стороны не подняться". Это всегда заставляет волноваться. "Нет, тут не подняться, слишком круто, никто тут еще не прошел". По правде говоря, вряд ли кто-то прошел хоть с какой-нибудь стороны, ведь этот небольшой район с четырьмя высочайшими вершинами Nyainqentangla, окруженный тысячей миль с востока и запада, был загадкой, сюда очень сложно получить пермит, требовался какой-то трюк, колдовство, но йоркширцу, сидящему справа от меня, каким-то образом это удалось. Прошло несколько дней, и настало время акклиматизироваться и осмотреть район, который предстоит открыть. До сих пор мы видели только несколько фотографии, сделанных с большого рассстояния Томом Накамура, отличные снимки, поражающие воображение, но они не отражали район по-настоящему, а лишь дразнили возможностями, и поэтому мы сейчас должны пройти семь-восемь миль, чтобы включиться и начать знакомство. Был очевиден путь по ребру Nyainqentangla I, но что дальше? В переписке перед экспедицией Пол часто упоминал огромную Северную стену, почти не видную на фото, но на Google Earth она просматривалась, и, вроде бы, здесь могли быть возможности. Мы вышли из базового лагеря с грузом, достаточным на несколько дней. ВС был на высоте 5000м, поэтому мы остановились на небольшой травянистой поляне за моренной грядой, с ручьем и яками, на 5400 м. При взгляде на четыре семитысячника, два из которых были, по сообщениям, нехоженными, возможный путь просматривался лишь в нижней части одного из монолитов, который местные жители называли к Nyainqentangla юго-восточная, и этот склон очень заинтересовал Пола.

На второй день акклиматизации мы поднялиь чуть выше, пока большие птицы кружили высоко над головой, прежде чем в конце концов поставили лагерь во второй половине дня. Сокровенная стена открылась, драматичная, треугольная, нависающее чудо... Между Полом и мной проскочила искра. Эту стену, эту нехоженную стену на нехоженной горе было почти невозможно описать без использования превосходной степени, это был сон, это были ручейки, лед, снежные поля, aretes – стена чем-то напоминала массивного монстра Маттерхорн, и мы поняли, на том самом месте, что восхождение начнется на 5400m и до вершины 7046m, по стене 1600 м. Мы с Полом стояли и строили воображаемые линии, больше не нужно было ничего искать.

Погода была сложная. Почти каждый день было солнце, дождь, снег, ветер, слякоть, туча, гроза, град. Ни один день не был похож на другой, и, как правило, текущей погоды хватало ненадолго, пока не проявлялся какой-либо другой метеорологический выверт. Мы не планировали для этого восхождения ждать пятидневного "окна" приличной погоды, потому что у нас не было источника прогноза, мы рассчитывали только на себя. И сидеть в ожидании было не очень желательно, хотя мы надеялись, что "окно" наступит. .

checking it out on the acclimatisation. Pic credit, Paul Ramsden. Акклиматизация. После пяти дней акклиматизаци, в т.ч. с плохой погодой, в т.ч. с отдыхом (для меня), мы с Полом собрали вещи и поднялись в долину. Разбив лагерь под треугольной стеной, ощутили свою мизерность. Стена была огромной. Ночью шел град и выпало несколько дюймов снега. У нас был запас времени, поэтому мы оставили снаряжение и сбежали обратно, но не надо забывать, что это была экспедиция Рамсдена, а Рамсден не был расположен ждать, поэтому только один день отдыха - и мы вновь разбили лагерь под стеной. В этот день подхода мы были награждены первым полностью солнечным и сухим днем с самого момента прибытия, и это должен был быть знак, сигнал от богов, сулящий удачу, но, конечно, такого не случилось, это была просто еще одна случайно выпавшая карта из мешка погодных сюрпризов этого района. В первый день был глубокий рыхлый снег, и много всего, в целом день получился драматичный и захватывающий. Мы начали восхождение, и вновь погода была приличная, и хотелось бы, чтобы продержалась такой еще хотя бы день, глядя вверх на крутой и технически сложный путь, который мы уже мысленно считали ключом, с крутыми, местами нависающими ледяные речками.

Myself taking the turn to put in a track the evening before… pic, Paul Ramsden.

Paul on day one. Pic. Пол, день первый.

Myself, day two. Pic credit, Paul Ramsden. Ник, день второй День второй. Вид из открытой палатки торопил нас стартовать достаточно рано. Через несколько часов я пролез верхнюю часть, очень сложную, гнилой, нависающий лед. Пол подошел ко мне, и мы решили, что пора здесь остановиться на ночлег.

Myself approaching the steep stuff, day two. pic credit, Paul Ramsden. Ник, день второй.

Paul on one of the steeper sections day two. Пол, день второй.

An excellent night was had by all! Paul happy with his tent and hammock. Третий день был коротким и решительным. Мы изначально наметили линию, соединяющую три ледовых поля с правой стороны, но после первого и тяжелого второго дней, нас одолевали сомнения, и в конце-концов, мы склонились к снежной полке, ведущей влево прямо на очевидный контрфорс, т.е. это был прямой путь к вершине.

Paul traversing to my position, day three. Пол траверсирует.

Мы закончили рано и выкопали небольшую лощадку, которую увеличили сеткой для снега - нарастили выступ еще больше. Пол поставил палатку, радуясь таланту своей тещи, которая сшила специальный брезентовый лист, который сейчас был закреплен на якоре с помощью ледобура и поддерживал дополнительный снег, увеличивая полочку. Вечером пошел снег, мокрый снег, град, сопровождавшийся сильными порывами ветра, типа, "наш отпуск закончился". Четвертый день был довольно долог, мы оставили наш лагерь на месте, и поднялись до 6700m и снова построили снежный выступ благодаря синему брезенту, скроенному далеко в Ноттингеме. Снег бушевал всю ночь.

More lung busting on day five. Больше перебора легких на пятый день.

Пятый день. Пятый день. Что о нем рассказать, кроме того, что на пятый день шел снег, а потом светило солнце, прежде чем ветер усилился еще до того, как Пол и я стояли на вершине в полдень. Я признаюсь, был очень счастлив. Пол тоже был счастлив. Погода была не слишком плохой, и идея спускаться по линии подъема (в случае плохой погоды) была отвергнута. Поэтому мы пошли траверсом до Восточного гребня к в его высшей точке, чтобы затем повернуть налево к бесконечным снежным полям обратно к "своей" долине и " нашей " хорошо знакомой морене и, наконец, к базовому лагерю.

Summit Selfy.

И тут, как по команде, тучи решили завернуть нас в наших мечтах, но, будто почтовый голубь, Пол шел решительно через ребро и вниз через сомнительные снежные склоны. Облака стали еще гуще, снег белее, крутизна больше, рельеф более опасный и, после того, как пересекли три бергшрунда, мы остановились, чтобы поставить палатку в одной из обнаруженных дыр. Я не боялся, мы уже побывали на вершине, и погода была не так уж и плоха. Если только облака разойдутся завтра утром, и мы найдем нужный кулуар, ведущий на северную стену, и траверс к нижнему гребню, и, наконец, к нашему снежному склону, выходящему на морену, т.е. к безопасности... и тогда все будет ОК. Сразу после наступления темноты пошел снег, и снег, и снег еще. Я лежал, не спал вообще, а думал, зачем мы не спускались по линии подъема? Теперь мы застряли где-то выше 6500м в бесконечных снегах, еда кончается, и непонятно, как выбираться. О чем мы думали? Мы поднялись по линии, мы выиграли, теперь мы где-то у черта на рогах, и можем погибнуть.

Наш Йоркширский почтовый голубь смог-таки найти вход в кулуар, ведущий от верхней кромки до нижней гряды прямо вниз по Северному склону. Способность Пола вынюхивать линии и проходить технические участки была поразительной, сказался и его возраст и весь его альпинистский опыт. В итоге, пройдя несколько серьезных плит, мы достигли нижней гряды, достигли точки , где надо было повернуть налево, но путаница ледяных дырок и нависаний изменила наш план, и мы повернули вместо этого направо, в Южную долину, пока не остановились на выполаживании. Седьмой день был долгий трудный, это не просто путь через нагромождение морен и речек, который после семи или восьми часов, привел нас обратно в реальность недалеко от деревни и дома, откуда мы начали, и дома, в котором остановился тибетские офицер связи.

I sat in our tent and blue stripe tarp, our makeshift home. Paul Ramsden sat nearby. To our left the fast flowing glacial river pounded grey rocks – rocks rubbed smooth by the constant grey flow. To our knowledge we were the first Westerners to explore this valley on the North on the Nyainqentangla peaks. “No, that’s not the side to climb from.” That one always makes me warm. “No that’s not the side to climb from, it’s too steep, no one has climbed from that side. Truth be told, hardly anyone had climbed from either side, the small sub-range range, which holds the four highest mountains in the whole of the thousand-mile East and West Nyainqentangla was an enigma, an unknown, a very difficult to get permission, a magician’s trick, but the Yorkshire man who was sat on my right had somehow managed it. A few days had passed and it was now time to acclimatise and see what the range revealed, what would unfold. Until now we had only seen a few long distance photos taken by Tom Nakamura, great shots that opened the imagination but none truly undressed the range, they teased with possibilities, but we would need to walk the seven or eight miles to become involved and begin this relationship. Day two of the acclimatisation came, we stumbled a little higher sending rocks splintering while large birds passed high overhead before eventually setting camp in the afternoon. The mystery face opened, it was dramatic, triangular, overhanging, a wonder… The charge between Paul and myself crackled. This face, this unclimbed face on an unclimbed mountain was almost impossible to describe without using superlatives, it was a dream, it had runnels, ice, fields of snow, aretes – the face twisted and turned in some warped massive monster Matterhorn way and we fathomed, from our position, that the climbing started at 5400m and the summit was a reported 7046m, making the face a mouth-puckering 1600m. Paul and I stood and weaved imagined lines, we didn’t need to look any farther for our objective. The weather in the range was complicated. Most days had sun, rain, snow, wind, sleet, cloud, storm, hail. No day was the same and mostly the weather of the moment only lasted for a little while before some other form of meteorological bruising took over. This climb was not going to be one of those wait for a perfect five-day forecast, which was OK, because we had absolutely no form of contact from which to get one, we were on our own. This climb was going to be a get involved and sit out the not so desirable until it hopefully passed. After the five days acclimatisation, some bad weather, some resting (for me), Paul and I walked up the valley with bags packed. Being camped beneath the triangular face made the word, insignificance, have meaning. The face was huge. In the night it hailed and snowed several inches. We had time, so we left all of the gear and ran away, but remember, this was a Ramsden trip and Ramsden does not really do waiting well, so after only one day of rest, we were again camped beneath the face. On this day of walking we had been granted our first full day of sun and dry since we arrived, it had to be a sign, a pointer from the gods, a good luck gift, but of course it wasn’t, it was just another card, an incitement pulled from the bag of weather tricks this range had in its pocket. Day one was deep powder, post holing, some steep, some run-out, some exploring, but always dramatic and thrilling. We were on our way and once again the weather was holding tight, although it had to, and it had to hold for at least for another day because looking up at the steep and technical to come, on what we had already christened the crux day, the thought of been in those steep, sometimes overhanging ice runnels with powder pouring was too much to contemplate.

Day two, an open bivvy encouraged us to set off reasonably early. Luckily the steep nature of the ground we climbed now had formed neve and did we needed it. Several hours later I pulled from the top of what first appeared to be an ice romp but what was in fact one of the harder pitches, which turned into a rotten, overhanging, lung straining, gut busting. Paul joined me looking a tad haggard for a Yorky and agreed we needed to bivvy. Day three was a short one and decisive. We had originally spied a line joining the three ice fields to our right but after the first and physical two days, looking right filled both our heads with doubt, it just wasn’t certain enough even for gamblers and looking to the left, at a snow shelf leading direct to the prominent rib that was a direct line to the summit, caught our vote. We finished early and dug a portion of fine snow arete which was enhanced by a cradle to catch the snow and enlarge the ledge even more. Paul happily pitched the tent enthusing the sowing skills of his Mother-in-Law, Di, who had constructed and sewn the sheet from which it was now was anchored by ice screws and supported extra snow to form a larger ledge. In the evening it started to snow, sleet, hail and gust, our sabbatical was over. Day five. Day five. What can be said about day five other than it snowed, and then the sun shone before the wind picked up before both Paul and I stood on the summit at midday. Setting off, almost immediately on cue, the clouds chose to wrap us in our dreams, but somehow, like a homing Pigeon, Paul led across ridges and down and around dubious snow-slopes stopping whenever the cloud turned pea-souper… I wasn’t worried, we had summited and the weather wasn’t that bad. If only the cloud would bugger off tomorrow morning, the hidden gully-exit we needed to find, which would lead to the North Face and the traverse to a lower ridge and finally our snow slope to the moraine and safety, we would be OK. Soon after dark it began to snow, and snow and snow some more. I lay, not sleeping at all, while admonishing myself for not forcing the issue and abseiling the line we had climbed. Now we were stuck somewhere teetering on a ridge above 6500m in a dump of snow with limited food and limited knowledge how to get off. What were we thinking? We had climbed the line, we had our prize, this was just the way off, it didn’t matter, it was a fucking way off, that’s all and it was going to kill us.

The Yorkshire homing Pigeon pulled a master stroke finding the exit gully leading from the upper ridge to the lower ridge via several abseils directly down the North Face. Paul’s ability to sniff out the line and cover technical ground was astounding, his years and years of Alpine climbing and the experience easy to see. Eventually, after covering several pockets of serious slab which chose to stay-put, we reached the lower ridge and after a few technical sections hit our turn left col, but the mess of glacial holes and lines and overhangs changed our plan, so instead we turned right into the south valley before stopping on flattening. Day seven was a long arduous day following no path just a jumble of moraine and a river which after seven or eight hours popped us back into some form of reality near the village and house from which we started and the house where our Tibetan Liaison Officer was staying.

Источник: http://nickbullock-climber.co.uk Перевод: Елена Лалетина (www.Russianclimb.com) |